Collection

Museo di Anatomia Umana (Museum of Human Anatomy) “Filippo Civinini”

On the ground floor, in the “Galleria dei Busti” there are six plaster busts of illustrious scientists, naturalists and anatomists who came to Pisa between the 16th and 19th centuries: Andrea Vesalio, Realdo Colombo, Lorenzo Bellini, Filippo Pacini, Bartolomeo Eustachio and Gaspare Aselli.

On the first floor, we find the Mascagni Gallery, which houses the precious anatomical panels by Paolo Mascagni. On the second floor, in the “Regnoli” and “Duranti” rooms, there are the anatomical and archaeological collections.

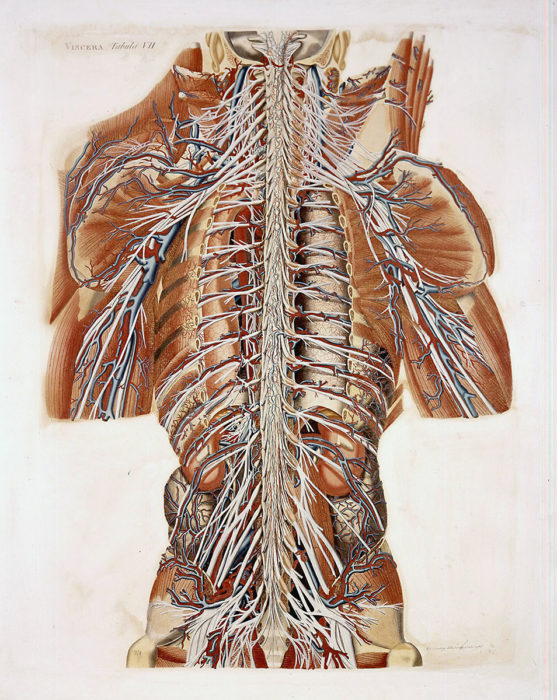

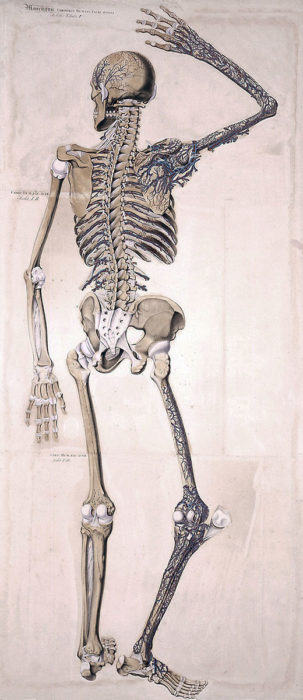

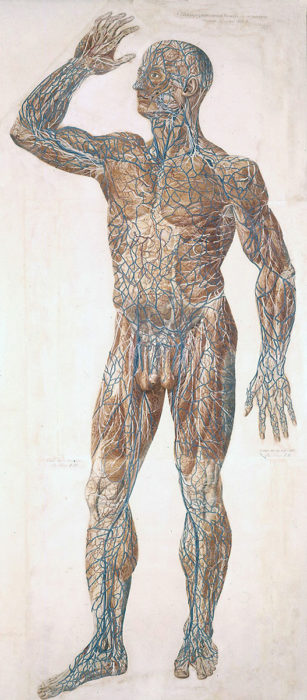

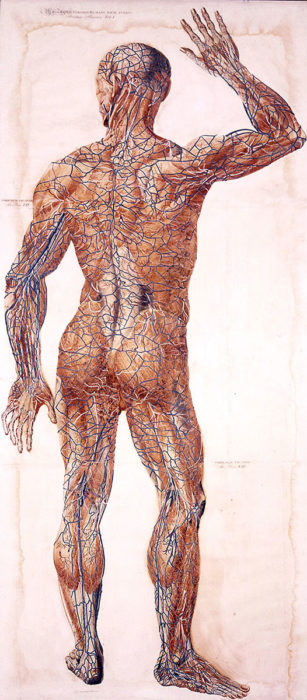

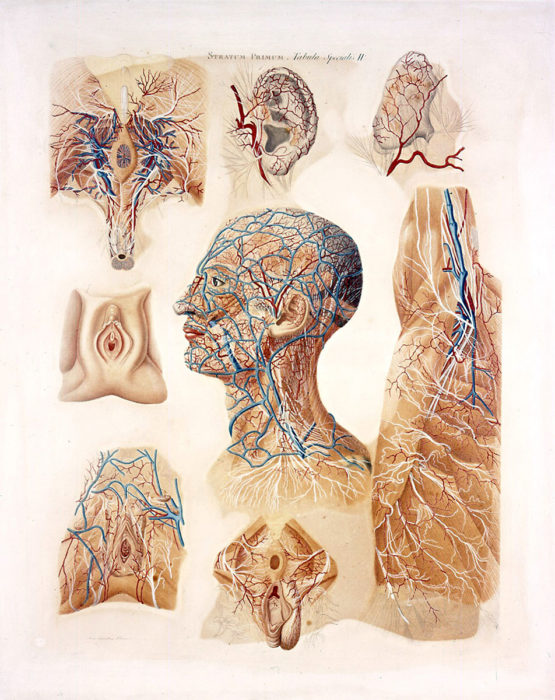

Mascagni’s tables

Paolo Mascagni (1755-1815), professor in Pisa in 1801, was born in Pomarance (Pisa) in 1755. When he was just 17 years old, he began his studies at the University of Siena and completed them in 1778 with a degree in “Philosophy and Medicine”.

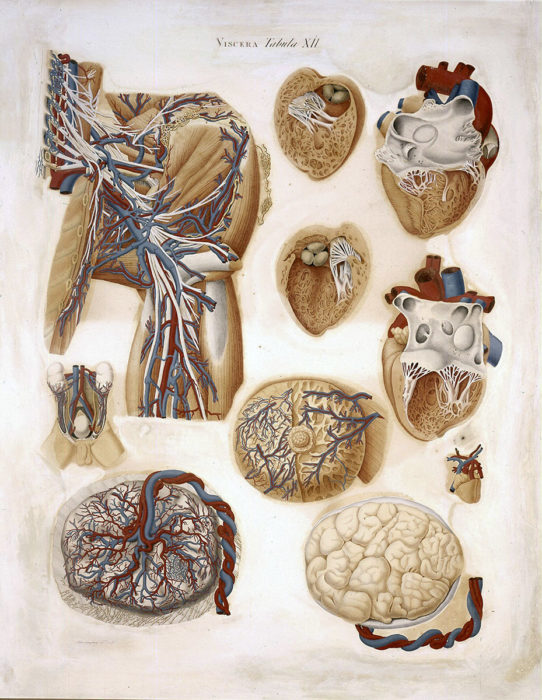

In 1787 he wrote the “Vasorum lymphaticorum corporis humani historia et ichnographia auctore Paulo Mascagni in Regio lyceo publico anatomes professor” complete with 27 plates and 14 contour counter-plates.

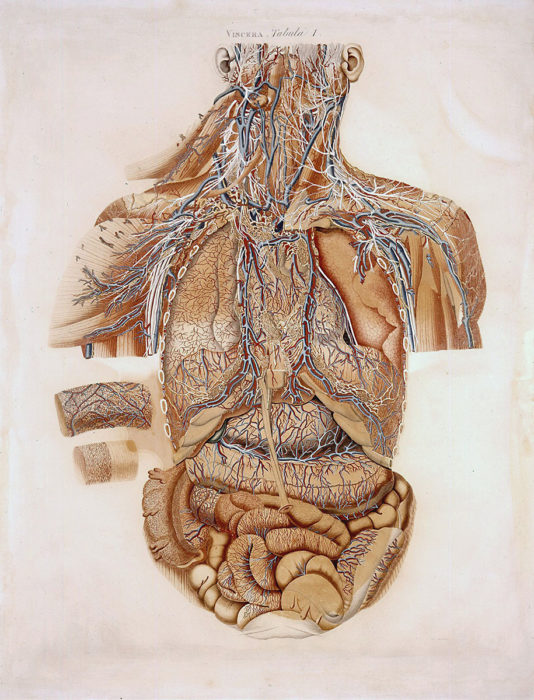

In this work Mascagni perfectly described the lymphatic system, ordering it and dividing it into individual systems. He also made discoveries that are still valid today, including the confluence of the lymphatic vessels in the thoracic duct and the direct communication of the arterial vessels with the venous ones.

The Work of a lifetime

From this first effort, he developed the idea of composing a life-size Anatomy of Man, starting a thirty-year work that would definitively consecrate him.

Mascagni worked tirelessly on his monumental work, great for inspiration and structure. The Anatomy Universe foresaw something never faced before, namely the representation of the human body in life-size.

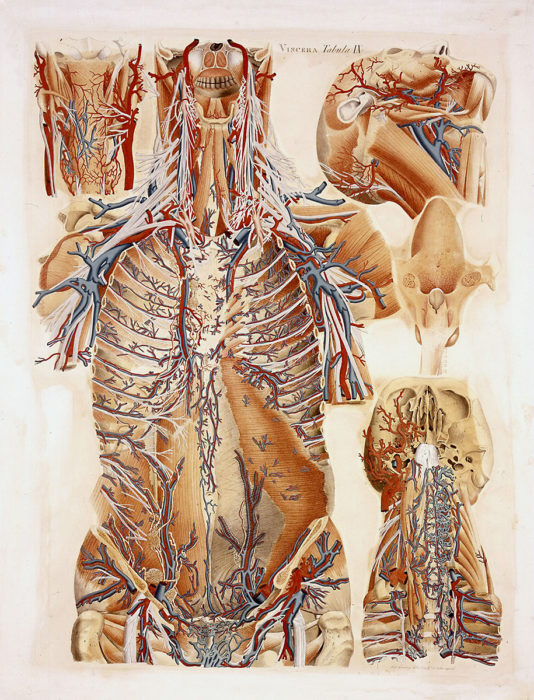

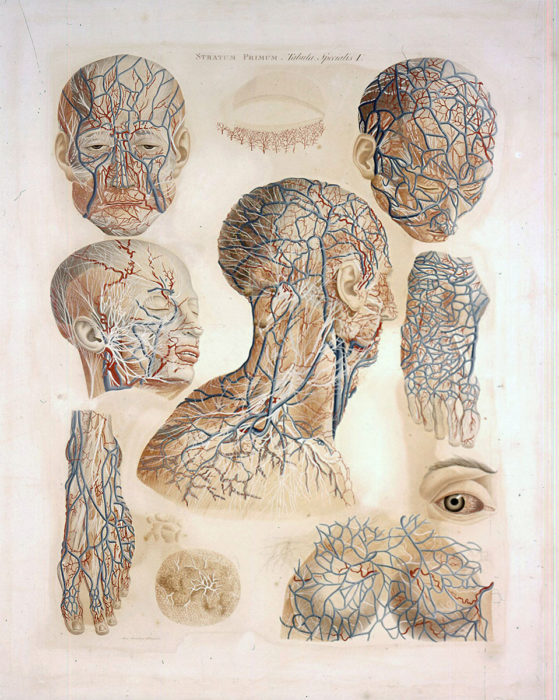

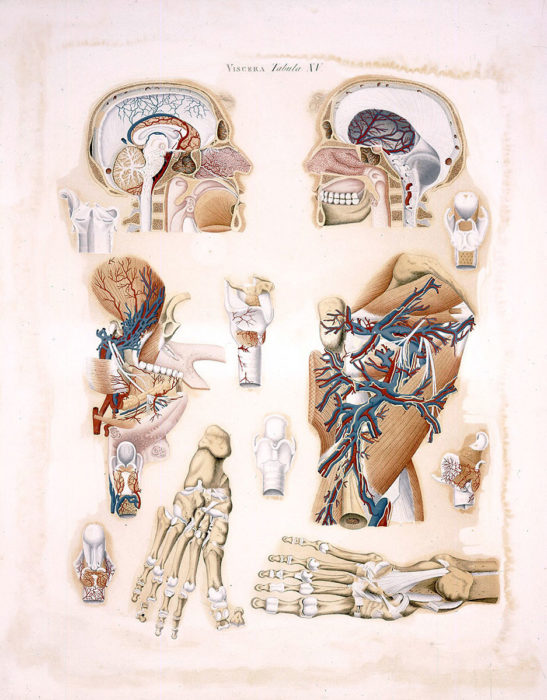

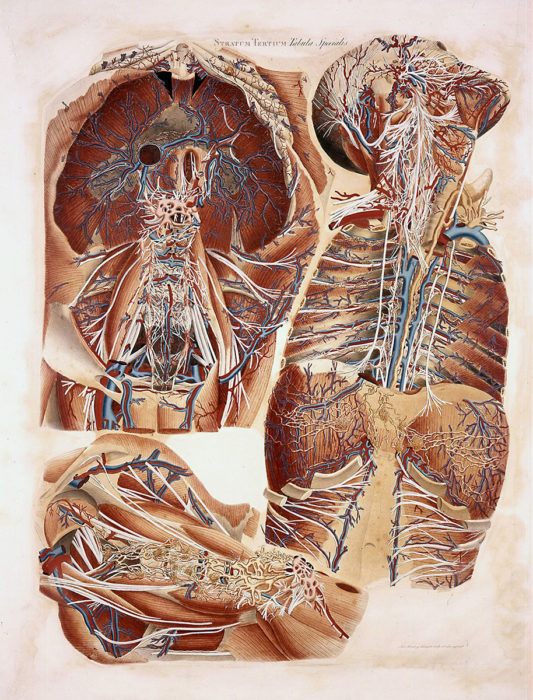

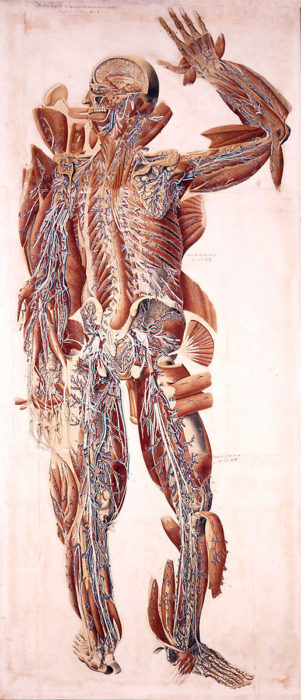

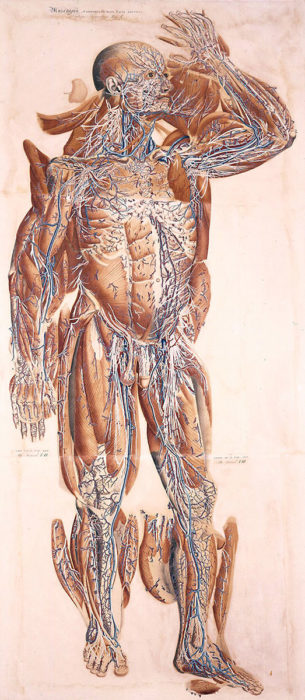

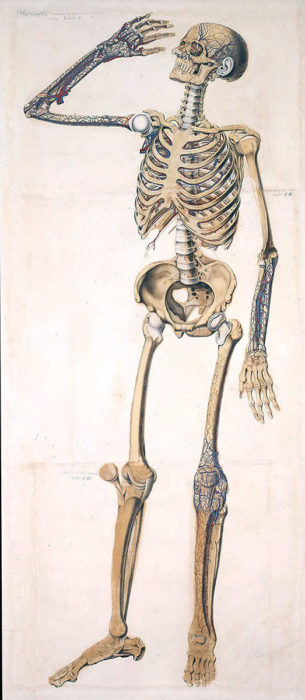

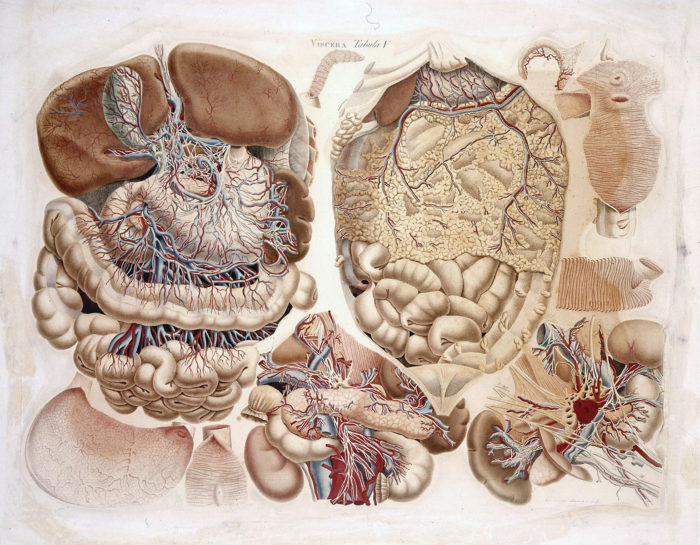

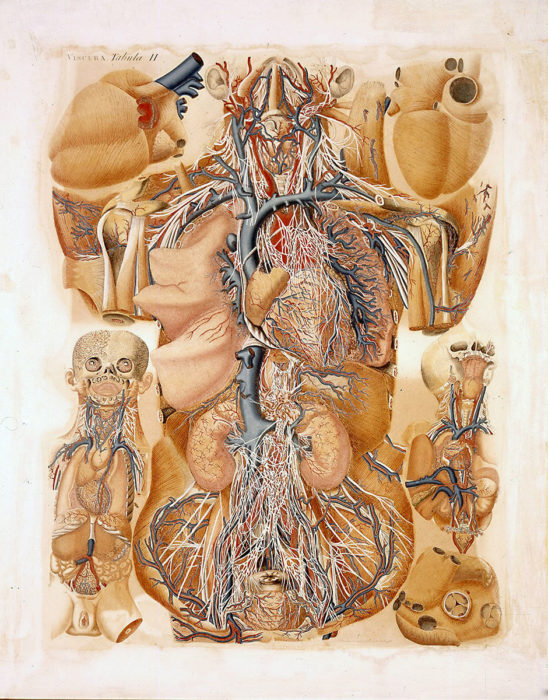

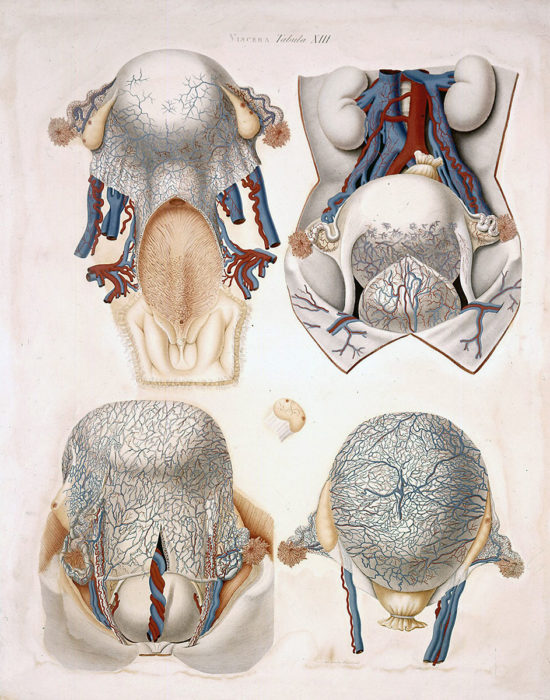

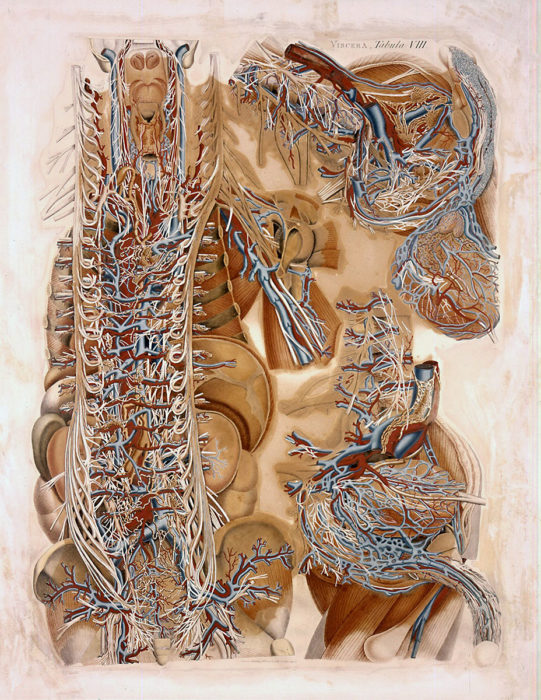

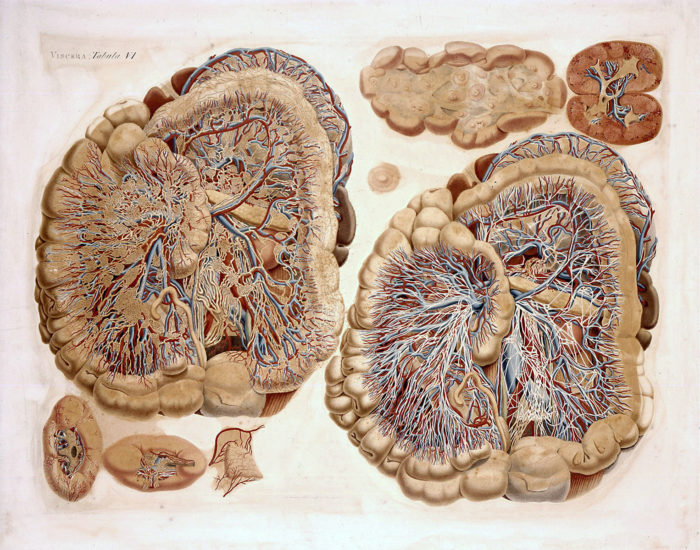

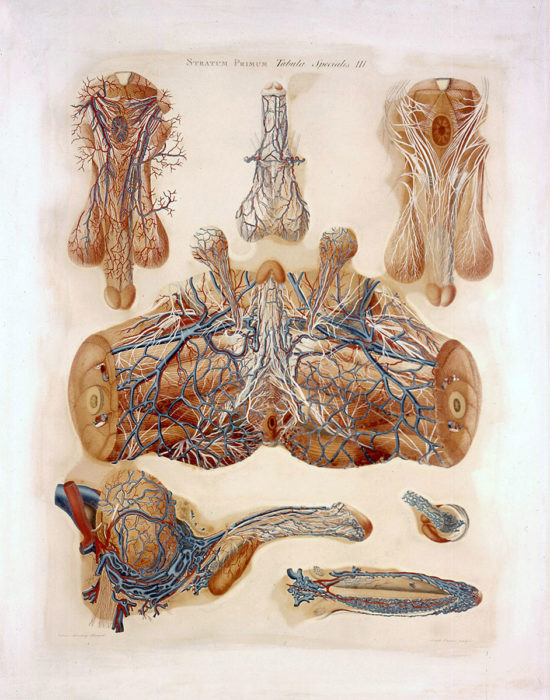

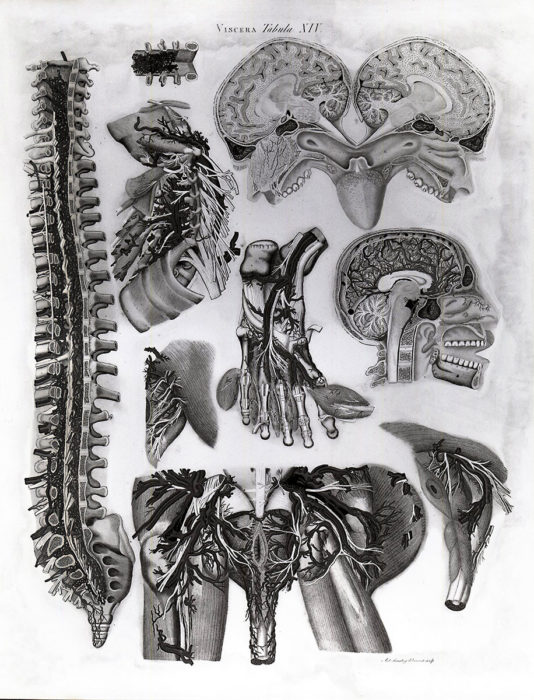

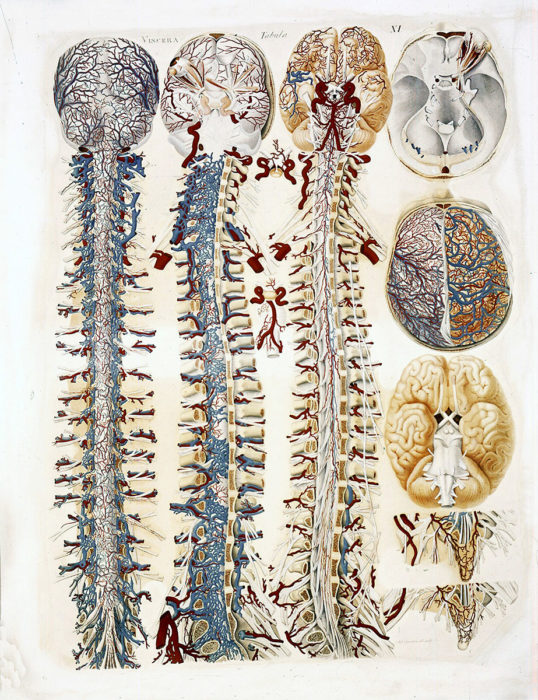

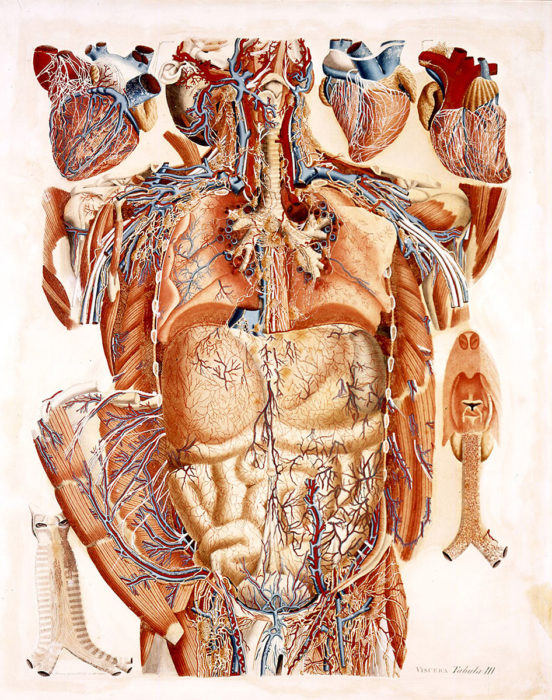

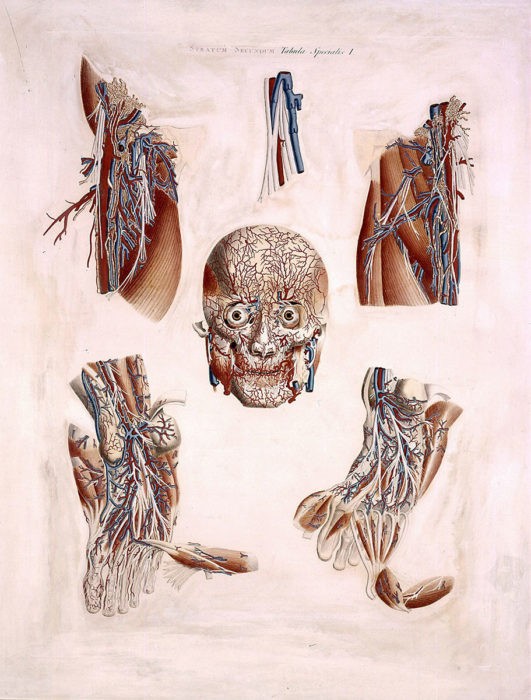

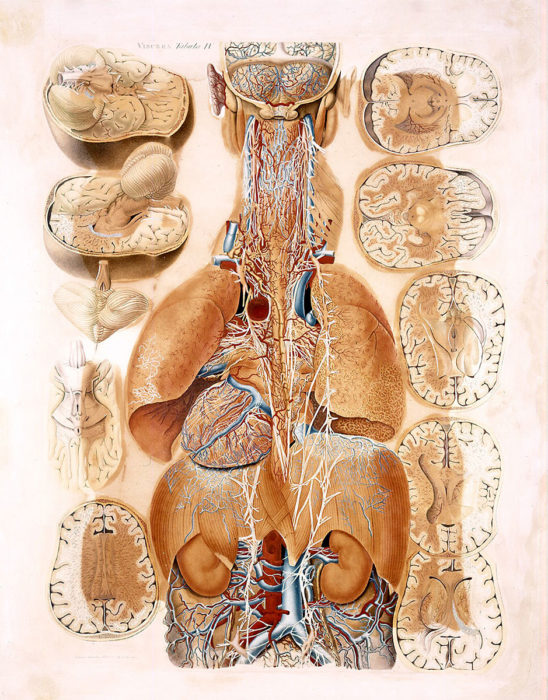

In his tables are represented both the front and the back of the human body, on several levels, following a stratigraphic criterion. From the superficial muscular plane we go to the intermediate one to the deep one (Tab. I, Tab. II, Tab. III), with 15 more plates for the viscera and 40 drawings for the anatomical parts not considered in the previous plates.

Although he worked tirelessly on it, when he died in 1815 his work was unfinished: the publication of the “Anatomiae Universae Pauli Mascagnii Icones” was posthumous and was completed in 1831.

It was immediately clear how it represented the maximum anatomical atlas, extraordinary for its breadth, commitment and realization and whose superb results can be admired along the Gallery of the Human Anatomy section.

Medical Collection

The Medical Collection of the Museum has several sections of preparations and findings.

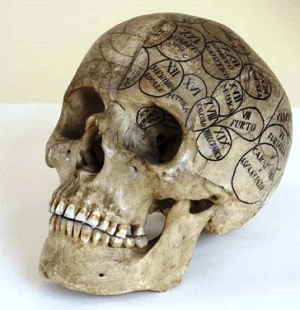

Of great interest is the Osteological Collection, from the whole skeleton to the single bones with some particularly valuable finds.

A rich section is also the Sindesmological one, which includes several preparations concerning the articulations between the bones and the ligamentous apparatus.

The section of Angiology boasts a considerable number of preparations about the heart and blood vessels made with the technique of embalming and injection with variously colored plaster.

In addition to the original preparations, the Museum has many anatomical models made of various materials including wax and plaster (for the older ones) and plastic materials (for the more recent ones).

Among the Embryological preparations there are several wax models that illustrate the most significant phases of human and animal development. In particular, there is a large model of human embryo that can be studied in its various sections thanks to a system of levers that break it down.

A rare collection of fetal skeletons completes the embryological part.

Archaeological Collections

The Museum has valuable archaeological finds from South America. This important pre-Columbian collection, which reached the Museum between 1860 and 1870, was collected in Peru thanks to the excavations carried out by Carlo Regnoli (1838-1873), doctor and scholar of the University of Pisa. Regnoli distinguished himself on several fronts: as a doctor he took part in the Third War of Independence where he treated wounded soldiers and, as an archaeology enthusiast, he carried out research both in Egypt and South America. In particular, in 1869 he made an important expedition to Peru from where he brought back pre-Columbian vases, botanical remains, some specimens of mummies and funerary objects.

In 1894, Baroness Elisa de Boilleau donated three boxes containing other pre-Columbian material to the then Civic Museum, which were added to the already existing Regnoli Fund.

In addition to the pre-Columbian finds, the Museum preserves an Egyptian mummy with the original sarcophagus, beautifully painted and in excellent condition. Its origin is presumably attributable to the Franco-Tuscan expedition to Egypt and Nubia in 1828-29 by Ippolito Rosellini, following Jean-François Champollion.

Vases

The pre-Columbian collection donated by Carlo Regnoli counts 121 vases from the pre-Columbian Chimù and Chancay cultures, dating back to a period between the 12th and 16th centuries. There are anthropomorphic, zoomorphic or phytomorphic representations. The same pre-Columbian collection also includes botanical and vegetable remains, mummies and funerary outfits (tools, bowls, cloths, etc.).

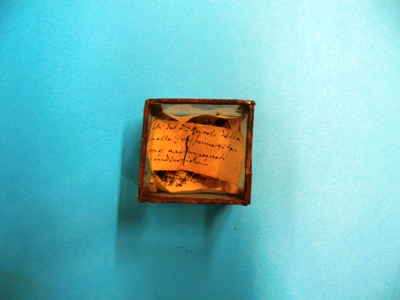

Funeral trousseaus

The boxes containing the Funerary Goods (tools, bowls, fabrics, etc.) are part of the finds collected in South America by Carlo Regnoli (1838-1873).

The entire collection was donated to the Museum, where it still resides.

.

L’intera collezione fu donata al Museo di Anatomia “F. Civinini” di Pisa, dove tuttora risiede.